Absolute masterpiece by @AatishTaseer. His piece on @ImranKhanPTI is essential reading today. https://t.co/2PaRKKqsqx

— Annie (@quratula1n_s) September 12, 2019

Imran Khan is like Michael Corleone right after his father died, one hand tied. He is in a very tight spot. He is head of state in a country where Benazir Bhutto was assassinated and Pervez Musharraf almost was: two attempts in one week while he was military dictator. Those who propose he take the terrorist bull by the horns should take note.

58 countries joined Pakistan in asking India to lift restrictions in Kashmir: Imran Khan

— Times of India (@timesofindia) September 12, 2019

READ: https://t.co/e0fLFGS5uc pic.twitter.com/6xszz1KdP0

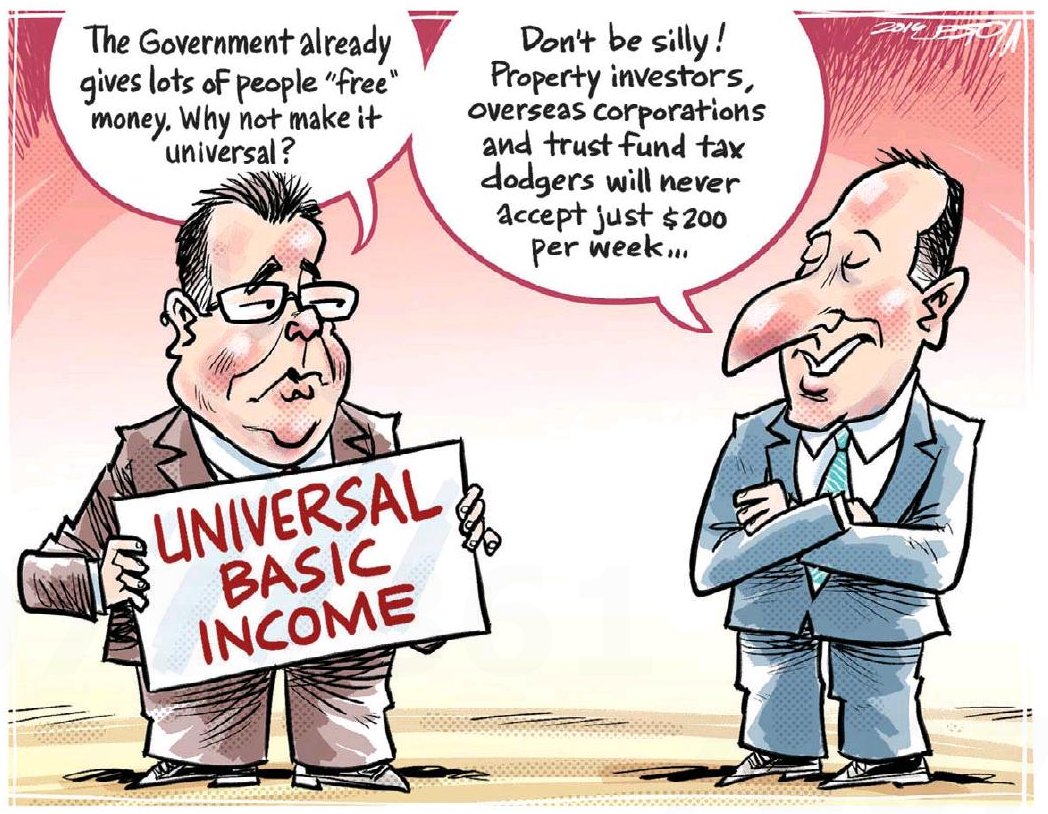

“For teams like Pakistan, India, and the West Indies,” Khan writes in his autobiography, “a battle to right colonial wrongs and assert our equality was played out on the cricket field every time we took on England.” Into this gladiatorial arena, shirt open, eyes bedroom-y, hair long and tousled, stepped Khan. He was one of those rare figures, like Muhammad Ali, who emerge once a generation on the frontier of sport, sex, and politics. “Imran may not have been the first player to enjoy his own cult following,” writes his biographer Christopher Sandford, “but he was more or less single-handedly responsible for sexualizing what had hitherto been an austere, male-oriented activity patronized at the most devoted level by the obsessed or the disturbed.” In 1996, after years of turning down pleas from established politicians and military dictators eager to align themselves with his celebrity, Khan launched his own political party. In its first election, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, or PTI—which translates as the Movement for Justice—won zero seats in parliament. Five years later, Khan won one seat, his own. Even by 2013, with his personal popularity at an all-time high, the PTI won only 35 seats. For 20 years, he had been telling his friends and well-wishers that “the next time you come to Pakistan, I will be prime minister.” But four elections had come and gone, two marriages had collapsed in their wake, and the quest of this aging playboy to be his country’s premier was no nearer its end. armor Pakistan against its own elites, whose “slavish” imitation of Western culture had instilled in them a “self-loathing that stemmed from an ingrained inferiority complex.” “An emotion that he feels very strongly about is that we should stop feeling enslaved to the West mentally,” said Ali Zafar, Khan’s friend and Pakistan’s biggest pop star. “He feels that since he’s gone there—he’s been there and done that—he knows the West more than anybody else over here. He’s telling them, ‘Look, you’ve got to find your own space, your own identity, your own thing, your own culture, your own roots.’ ” I first spoke with Khan at a party in London, when I was 25. At the time I was dating Ella Windsor, a minor member of the British royal family who was a family friend of the Goldsmiths. To see Khan out and about in London—the legend himself—was to understand how truly at home he was among the highest echelons of British society. The English upper classes adore cricket—it is one of the many coded ways in which their class system works—and the allure of the former captain of the Pakistani cricket team was still very real. The night we met, in late summer 2006, Khan had come to a party at a Chelsea studio overlooking the Moravian burial ground. On that balmy evening, surrounded by the silhouettes of plane trees, it was clear that Khan, five years after 9/11, was in the throes of a religious and political transformation. ...... He said he believed that suicide bombers, according to “the rules of the Geneva Convention,” had the right to blow themselves up. Here, I remember feeling, was a man who had dealt so little in ideas that every idea he had now struck him as a good one. Khan has a commanding presence. He fills a room and has a tendency to speak at people, rather than to them; never was there a greater mansplainer. What he lacks in intelligence, however, he makes up for in intensity, vigor, and what feels almost like a kind of nobility. ...... “You might say he’s a duffer; you might say he’s a buffoon,” his second wife, Reham, told me over lunch in London. “He doesn’t have intelligence of economic principles. He doesn’t have academic intelligence. But he’s very street, so he figures you out.” Like his coeval in the White House, Khan has been reading people all his life—on and off the field. This knowing quality, combined with the raw glamour of vintage fame, creates a palpable tension in his presence. The air bristles; oxygen levels crash. The line is taut, if no longer with sex appeal, then its closest substitute: massive celebrity. But to see him two years later in the old city of Lahore, doing more dips in the gym at 55 than I could do at 27, watching him fawned over by young and old men alike, was to feel myself in the company of a demigod. Alone with him, I was struck by that mixture of narcissism bordering on sociopathy that afflicts those who have been famous too long. His utter lack of emotion when it came to Bhutto—whom he had been at Oxford with, and had known most of his life—was startling. “Look at Benazir,” he told me as we drove through Lahore one morning, past knots of mourners and protesters. “I mean, God really saved her.” Then he began fulminating against Bhutto for having agreed to legitimize General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan’s military dictator, in return for the government dropping corruption charges against her. Now it is Khan who has been appointed, presiding over a government in which there are no fewer than 10 Musharraf-era ministers. Khan, Rushdie said, was “placating the mullahs on one hand, cozying up to the army on the other, while trying to present himself to the West as the modernizing face of Pakistan.” “You know me,” he said. “I’m a liberal; I’ve got friends in India; I’ve got friends who are atheists. But you’ve got to be careful here.” My uncle—the grandson of Muhammad Iqbal, Khan’s political hero Like evangelicals in the United States, in whom a politicized faith conceals an uneasy relationship with modernity and temptation, Khan’s contradictions are not incidental; they are the key to who he is, and perhaps to what Pakistan is. His hatred of the “ruling elite,” to which he belongs, is the animating force behind his politics. He faults reformers, such as Turkey’s Kemal Ataturk and Iran’s Reza Shah Pahlavi, for falsely believing that “by imposing the outward manifestations of Westernization they could catapult their countries forward by decades.” Khan may be right to critique a modernity so thin that it has come to be synonymous with the outward trappings of Western culture. But he is himself guilty of reducing the West to little more than permissiveness and materialism. When it comes to its indisputable achievements, such as democracy and the welfare state, Khan conveniently grafts them on to the history of Islam. “Democratic principles,” he writes, “were an inherent part of Islamic society during the golden age of Islam, from the passing of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and under the first four caliphs.” Khan is not the first Islamic leader to insist that all good things flow from Islam and that all error is the fault of the West. But to do so is to end up with a political program that is by necessity negative, deriving its energy not from what it has to offer but from its virulent critique of late-stage capitalism. “The life that had come to Islam,” V.S. Naipaul wrote almost 40 years ago in Among the Believers, for which he traveled extensively in Pakistan, “had not come from within. It had come from outside events and circumstances, the spread of the universal civilization.” Khan’s repurposing of Iqbal serves in part as an inoculation against the West, and in part as a cudgel with which to beat Pakistan’s elite. But it does not amount to a serious reckoning with the power of the West, or with the limitations of one’s own society. As such, it cannot bring about the “cultural, intellectual, and moral renaissance” that Khan yearns for. Under his version of khudi, people genuflect toward Islam but quietly continue to lead secret Western lives. “He’s a stooge of the army,” a journalist in Islamabad told me. The journalist, who has known Khan for years, once counted himself among the cricketer’s greatest fans. “I consider myself to be that unlucky person who built a dream about an individual and saw it shattered before my eyes,” he said. In 2013, after years of military rule, Pakistan finally achieved what it never had before: a peaceful transfer of power. These signs of a maturing democracy, however, posed a direct threat to the power of the military, which began, in the words of Husain Haqqani, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the United States, to develop the art of the “non-coup coup.” That, the journalist said, is “where the unholy alliance between Imran Khan and the establishment began.” The following year, Khan led what are called the dharna days—months of protest calling for the overthrow of Pakistan’s democratically elected government.Imran Is Playing A Very Difficult Game https://t.co/6cmje9EIy6 @ImranKhanPTI @PTIofficial @SMQureshiPTI @ImranIsmailPTI @AliHZaidiPTI @MuradSaeedPTI @PTIOfficialLHR @naziarubbani @PTIKPOfficial #Pakistan #ImranKhan #Kashmir

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) September 12, 2019