Cover of Rabindranath TagoreLetter from a Wife

Cover of Rabindranath TagoreLetter from a WifeRabindranath Tagore

(1861-1941)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabindranath_Tagore

Dear Husband and Your Lotus Feet:

We’ve been married for fifteen years, but I’ve never written you a letter. All these years, I’ve stayed close to you – you’ve heard me speaking and I’ve heard you; there has been no spare time to write.

Today I’ve come to visit the pilgrimage here by the ocean, and you’ve stayed back in your office. Your relationship with Calcutta[1] is like one between the snail and its shell. It’s fixed so deep on you that you haven’t ever applied for a leave of absence. The God of Fate has precisely had that plan; she’s approved my application.

I’m the middle bride in your family[2]. Today, after fifteen years, standing on the seashore I’ve come to realize that I have another relationship with my world and its god. That realization has given me courage to write this letter; it’s not really a letter from your middle bride.

The one who wrote my fate together with your family, the time when none other than him knew of it, in that childhood my brother and I fell ill with typhoid[3]. My little brother died, but I pulled through. All the girls in the village said, “It’s only because Mrinal is a woman she survived; men couldn’t get over with it no way.” Yama, the God of Death, is apt at stealing – he’s always keen on getting the precious.

I can’t seem to die. That’s exactly what I want to clarify in this letter.

I was only twelve when your uncle and cousin came to see me as a potential bride for you. We lived in a remote village; you could hear foxes howling even in daytime. From the train station, one would reach our village by riding seven miles in a horse cart followed by three miles in a hand-held carriage, that too on a mud trail. Did you all have a hard time doing it! On top of it was our frumpy country cooking, which your uncle wouldn’t spare to mock even today.

Your mother was desperate to complement the lack of beauty in the eldest bride with the next one. Otherwise, why’d you even take so much trouble to visit such a remote village? In Bangladesh, nobody would be in the lookout for malaria, jaundice and brides – they’d come voluntarily and would never want to go away.

My father’s heart pounced; my mother began praying to Goddess Durga. How would a country devotee please an urban god? The only hope was the bride’s beauty; but the bride herself would not brag about it, and it was up to the buyer to settle on her price. Women would never be rid of their humility even with all their virtues.

The fear and apprehension of my family, in fact of the entire village, bogged me down like a boulder on my chest. Strangers were inspecting a twelve-year-old girl that day using all the powerful searchlights of the world – I had no place to hide.

Music of melancholy played across the sky – I arrived at your home. Having thoroughly criticized all the flaws I had, the group of elderly women agreed that overall, I was pretty. Elder sister-in-law of course went somber. I wondered though what the real use of my beauty was in the first place. Beauty would be worthwhile had an ancient priest created it using soil of the Ganges[4]; because God had created it out of bliss, it had no value whatsoever in your world and its concept of virtue.

It didn’t take you much time to forget that I was beautiful. However, you frequently remembered that I had intelligence. That intelligence I had was so natural that in spite of going through your mundane, household grind, it still breathed. My mother was very worried about my intellect – for poor women, it could always be a problem. For her who must comply with all the restrictions would one day sure be out of luck if she also complied with reasoning. But what else could I do? God gave me way more intellect that a bride in your family would ever need – now whom could I return it? You kept calling me the know-all dame. Harsh words would always be the weapon of the inept; therefore, I forgave you.

None of you had ever known that I had another element with me outside of the household chores. I wrote poetry secretly. Whatever rubbish it was, your walls could not build there. That was my freedom; that was where I was I. You’d neither liked nor recognized whatever in me was beyond your familiar middle bride; you’d never known in fifteen long years that I was a poet.

Out of all the memories in your home the thing that would come first was the cowshed. The cows lived right next to the staircase to go up in the women’s interior of the house; they had no place to move about other than the small square out in front. There was a wooden bucket in the corner for their fodder. The servants had errands to do in the morning; the starving cows would frantically chew up on the edges of the empty buckets. I couldn’t bear it. I was a country girl – the two cows and their three calves were the most familiar things to me when I first came to live here. I’d feed them out of my own food when I was a new bride; after that, others began to make oblique remarks about my kindness to animals.

My little girl died right after birth. She’d even called me to come along with her. If she lived, she’d bring me all the truth and nobility; I’d be promoted to be a mother from a wife. I got the hurt of motherhood, but not the emancipation that would come with it.

I remembered how the English doctor was shocked to see the women’s interior and condition of the labor room, and scolded you. You had a small garden in front of the house; there was no lack of decorative furniture in your rooms either. Yet, the interior was like the flip side of a silk stitch quilt – it was drab, barren and ugly. Neither light nor air would enter in it freely, trash would keep piling up in the corner; the walls and floors would remain as grimy as ever. The doctor, however, made a mistake: he thought the horrible conditions actually made us sad and miserable. But it was just the opposite. Carelessness would often be like ashes: they’d keep the fire hidden inside but wouldn’t let others know about the heat. In a forever dishonorable situation, lack of care would not hurt that much. In fact, that’s why women would feel embarrassed to feel pain. I’d say: if your system was such that women must feel pain, then you’d better keep them in constant negligence; otherwise, pain would worsen amidst care.

However way you let me live my life, I never wanted to think that I was unhappy. Death came to the labor room to take me away, but I was not afraid. Life didn’t mean much; so I never feared for death. Only those would have trouble to die whose life was deep-rooted in affection and care. If the God of Death had pulled me, I’d come out easily just like a patch of grass. Bengali women would die often, and die regularly. But what would be so dignified about it? It’d be so easy for us that we’d actually be shy about it.

My little girl rose briefly in the sky like the evening star and then quickly set. I went back on my daily rituals and chores with the cattle. Life would just roll on ‘til the end; I wouldn’t need to write you this letter at all. However, wind sometimes would blow a small, insignificant seed and drop it in the cracks of an edifice to germinate; in the end, the concrete structure would split open because of it. A small grain of life flew from nowhere and dropped in the middle of our family establishment; the split started to grow ever since.

After her mother passed away and cousins began abusing her, Bindu, sister-in-law’s younger sibling, came to take shelter in our extended family. You all were visibly disturbed considering it to be a hassle. Stubborn like anything I was, seeing how much disturbed you’d all felt, I came by the side of this helpless girl with all my force. It was already too disgraceful to live with somebody else’s family against their will. How could I ignore her pain and suffering?

Then I noticed the situation of sister-in-law. She’d brought her over out of sheer desperation. But when she saw how unsupportive her husband was, she started acting as if Bindu was indeed a big trouble, and that she’d find no problem whatsoever to kick her out. Devoted to the husband she was, it would be impossible for her to show any sign of mercy to her own little, orphaned sister.

I felt pain to see her predicament. I saw that just to satisfy everybody, sister-in-law gave her the worst possible food and put her in to work as a maid. I was ashamed. She started to make it a point that finding Bindu to do household chores – big or small – was indeed a cheap deal – that she practically cost nothing.

In sister-in-law’s parents’ family, there was absolutely nothing to show off other than their so-called blue blood. You all knew how she was married off into your family literally by begging, praying and going through utter humiliation. She always considered her marriage into this family to be a horrible wrongdoing. Therefore, she’d always kept herself concealed, taking up as tiny a place as possible in the extreme interior.

However, her exemplary lifestyle put us in jeopardy. I could never humble myself that much in all imaginable ways. If I knew something was good, nobody could easily convince me that it was bad – and you found various instances of this.

I took Bindu in my room. Sis-in-law complained, “Middle Bride will spoil the poor man’s daughter to death.” She started complaining about me all around. But I knew for sure that she felt greatly relieved. Now the burden of crime came upon me. She was relieved to see that Bindu had finally found some care, some affection from me – things that she could never give her. She’d often hide Bindu’s real age to make her look younger. Actually, Bindu was so cumbersome and awkward that if she ever fell on the floor and broke her head, people would first tend to the floor before minding her. Hence, without the presence of her parents, there was nobody to arrange for her wedding; it was also impossible to find a brave man who’d come forward and take her as his bride.

Bindu came to live with me with great trepidation as if I couldn’t tolerate her remotest touch. She thought she had no reason to live in this world; she’d avoid everyone and bypass all. In her father’s family, her cousins would never spare a little corner for her where nobody else could even leave unwanted items. In fact, unwanted items would easily find room in far and near corners of a home because people would forget them, but an unwanted woman would not find even a dump because first she was unwanted, and then, she could not be forgotten. Nobody could vouch that Bindu’s cousins were particularly wanted or needed in this world either. However, they did just fine.

So, when I brought Bindu into my room, she became very nervous. I felt very sad to see her fear. With great effort and affection I convinced her that she’d indeed have a little space in my quarters.

But my quarters were not my quarters alone. My task therefore didn’t turn out to be easy. Within a few days, she developed some red rashes on her body – they could be heat prickles or something similar. But you all said it was smallpox. Because it was none other than Bindu! An apprentice doctor from your neighborhood came and said, “Can’t tell without waiting for a couple more days.” But who’d wait at all? Bindu felt like dying out of embarrassment. I said, “Let it be smallpox. I’ll stay with her in that small labor room; you don’t need to do anything.” And then, when you were all furious with me, and Sis-in-law herself got terribly shaky and proposed to send her out to the hospital, her rashes disappeared. You said, “That smallpox must’ve buried inside the skin.” Sure, because it was none other than Bindu.

One of the big pluses of growing up in total lack of care was that it’d make you extremely strong. No illness could strike you, and all the roads to die would be totally closed off. The disease came to poke fun at her, but nothing else happened. But it was indeed clear that finding help for the most unwanted person in the world was the hardest thing to do. She needed the maximum protection; she had the maximum obstacles to it instead.

When Bindu finally broke her apprehensions about me, she grew yet another problem. She started loving me so much that even I was frightened. Did I ever see such an image of love in my entire life? Of course I read about it, but it would be between a man and a woman. The awareness that I was beautiful didn’t occur back to me in a very long time – now after so many years, this ugly girl brought that subject up. She wouldn’t stop looking at me. She said, “Sister, nobody else but me has ever looked at your face.” She’d be upset if I did my own hair. She’d find much pleasure to play with the volume of my hair. I’d never have any reasons to dress nicely unless there was a party outside. Now Bindu would make me irritated and dress me up every single day. She went wild with me.

There was not a single open space in your interior. There was a wild pome tree near the sewer by the northern fence. I knew it was spring when the tree showed bright-red budding leaves. In my quarter, I saw the uncared-for girl’s heart turning colorful; I knew there was spring in the world of hearts, and it came from the heavens, not from some dark alley.

Bindu made me annoyed with her deep care for me. Sometimes I’d be angry at her, still, through her affection, I saw a new me unfolding – something I’d never seen in life. It was a liberated me.

On this side, however, the fact that I was taking so much trouble for someone like Bindu was not well taken by you. Everybody would begrudge and bemoan about it. The day I lost my precious necklace, you’d never hesitated to declare that it was Bindu who’d done it. When the police came to search for suspected freedom activists[5], you’d all suspected that it was Bindu who had been the police spy. There was no other evidence for it: the only evidence was that it was Bindu.

Your maids would always object to do anything for her; she too would be frozen if someone volunteered to help. Naturally, my expenses went up: I employed a private maid. You didn’t like it at all. You were so upset to see the clothes I gave Bindu to wear that you stopped paying for my allowances. I started wearing cheap and coarse locally made clothes from the next day. I also asked Moti’s Ma not to come anymore to do my dishes. I’d feed my cow with the leftover rice and then do the dishes myself. You were not pleased to see it either. I could never grapple with the simple truth that it was always okay not to please me and it was never okay not to please you.

You got angrier and Bindu got older; even that very natural phenomenon disturbed you. The one thing I kept wondering about was why you hadn’t kicked her out by force. I knew deep inside that you actually feared me. At the end, because you couldn’t force her out yourselves, you sought help from the god of matrimony. Bindu’s groom was arranged. Sister-in-law said, “What a relief! Goddess Kali saved our family reputation.”

I didn’t know how the groom was; I just heard that he was good. Bindu fell at my feet and wept, “Sister, why’s there so much fuss about my marriage?”

I convinced her, “Bindu, don’t you worry – I hear that your man is nice.”

Bindu said, “Why’d a nice man choose someone as worthless as me?”

The groom’s family never even came to see Bindu before the wedding. Sister-in-law was greatly reassured by it.

But Bindu kept crying days in and out. I knew what pain she was bearing. I had fought hard to save Bindu, but could not have the courage to keep her from getting married. How in the world would I do it? What’d happen to her – a poor, dark woman – if I died? I was terrified to think about it.

Bindu said, “It’s still five days left before the wedding; couldn’t I die?”

I firmly rebuked her, but only God knew I’d actually feel a lot comfortable if she could die in a simple, straightforward way.

On the day before the ceremony, Bindu told her sister, “Sis, I’ll live in your cowshed, I’ll do anything you want me to do, but please don’t throw me out this way.”

Sister-in-law also was crying for a few days now, and today she cried too. But it was not merely a matter of heart; it was now a matter of social dictates. She said, “Don’t you know Bindi, a husband is the ultimate way for a woman to find happiness. And no one can stop you from being unhappy if that’s what is written for you[6].”

The truth was that there was no other way; Bindu must marry – whatever will be, will be.

I wanted the wedding to take place at ours. But you decided against it; you said it must be at the groom’s because it was their family tradition.

I realized that your family gods would never allow taking on the wedding expenses. So I remained silent. But none of you knew one thing: I secretly dressed Bindu up with some of my own jewelry. Maybe, Sister noticed it, but pretended not to. Please forgive her for this moral turpitude.

Before she left, Bindu embraced me and said, “So you really decided to give me up?”

I said, “No Bindi, whatever happens to you I’ll never give you up.”

Three days went by. In the morning, I went in to the tiny, thatched coal room to feed the lamb I saved from slaughter and hid. I found Bindu sitting there on the floor. She fell on my feet and wept silently.

Bindu’s husband was a mad man: a total lunatic.

“Are you telling the truth?”

“How can I tell such a lie to you, Sister? He’s insane. My father-in-law didn’t want this marriage to happen, but he was scared of my mother-in-law to death. He’d left for Kashi[7] just before the wedding. Mother-in-law insisted that her son be married.

I squatted down on the heap of coal. Often, a woman would find no mercy for another woman. She’d say, “She’s only a woman, after all. A man – crazy or not – is a man nonetheless.”

Bindu’s husband wouldn’t act like crazy all the time, but sometimes he’d go so out of control that they’d lock him up. He behaved nice on the wedding day, but because of the sleeplessness during the ceremony, etc., he went berserk the next morning. Bindu was eating rice from a brass plate; suddenly her husband yanked it and threw it out on the courtyard. Out of nowhere he thought that Bindu was Rani Rasmoni[8], the servant stole her gold platter, and put rice for her on his own brass plate. It made him mad. Bindu was petrified. On the third night, when the mother-in-law ordered her to sleep in the husband’s room, she was a nervous wreck. The mother-in-law was a very irate person; she’d be out of control in anger. She was crazy too, but not completely; that’s why she was ever more dreadful. Bindu had to enter the husband’s room. He was calm that day. But Bindu was stiff as wood in fear. When the husband slept, she somehow managed to escape; one didn’t need to write all the details of it.

I was burning in contempt and anger. I said, “This is a fraud marriage, not a real one. Bindu, you live here just like before; let me see who can take you out from here.”

You all said, “Bindu is lying.”

I said, “She’s never lied.”

You said, “How do you know?”

I said, “I know it for sure.”

You tried to scare me, “Bindu’s in-laws will go to court and we’ll all be in trouble.”

I said, “Wouldn’t the court understand that they tricked her into marrying a crazy man?”

You said, “So we have to fight a court case on it? What’s our problem?”

I said, “I’ll sell my ornaments and do whatever I can.”

You said, “Will you run up to the lawyer?[9]”

I couldn’t respond. I could bang my head hard on the wall, but nothing else.

Bindu’s elder brother-in-law came and raised hell. He’d threatened to go to the police.

I had no real power at all, but I simply couldn’t accept that I’d have to return the calf that fled from the slaughterhouse and came to me for its life. I said rather stubbornly, “Let him go to the police.”

Having said it, I thought this would be the perfect time to bring Bindu into my bedroom and lock her in. But I couldn’t find her anywhere. Finally I discovered that when I was arguing with you, Bindu went straight up to her brother-in-law and surrendered. She’d realized that her staying back in this house would put me in serious trouble.

The episode of running away worsened her misery. Her mother-in-law bickered that her son didn’t kill her or anything. She said, compared to many other abusive husbands, her son was like an angel.

My sister-in-law said, “She has bad luck; what can we do about it? After all, crazy or not, it’s her husband.”

You’d perhaps been thinking about the epic tale of the woman who’d brought her leper husband over to the prostitute. You men would never stop repeating this story – one of the most horrendous cowardice, and that’s why you’d never stop being angry about Bindu and her behavior so unacceptable to you. I was heartbroken about Bindu, but I was ashamed of you. I was only a village girl, and that too, given to people like you; how in the world did God slip in me so much power to reason? I could never put up with the bogus religious tales of yours.

I was certain that Bindu would never return. But I gave her my word that I’d never give up on her. My younger brother Sarat studied in a Calcutta college; you knew how enthusiastic he was about all kinds of volunteer work – be it fundraising for the flood-stricken or trapping the Plague moles. He’d actually failed exam because of spending too much time on philanthropy and no time to study. I called Sarat up and said, “You must do something so that I hear from Bindu. She’ll not dare to write me, and even if she does, the letter will never reach me.”

Of course, Sarat would be much happier if I’d told him instead to bring Bindu over by force or break her husband’s neck.

I was discussing it with him; at this time, you entered the room and said, “What problem have you caused now?”

I said, “The one and the only – I came to live here with your family – but it was your act, not mine.”

You asked, “You hide Bindu again?”

I said, “If she’d come, of course I’d have hidden her. But she’s not going to come, so don’t worry.”

Seeing Sarat, you grew even more suspicious. I knew how much you disapproved of Sarat visiting me. You were always worried that because Sarat was under the watch of the police, some day he’d be incriminated on a political crime and then all of you would be dragged into it. For that reason, even on Bhai Phota[10], I’d send the blessing over to him through attendants, but never invite him over.

But I learned from you that Bindu had run away one more time, and her brother-in-law came to search for her again. I was very worried to hear it. The poor girl was so helpless, yet I had no way to help her.

Sarat rushed to find out. He returned in the evening and said, “Bindu left and went back to her cousins, but they were totally upset and brought her back to her in-laws right away. They still couldn’t accept that they had to take in financial loss for the trip.”

Your aunt came to your house on her way to the pilgrimage by the ocean. I said, “I’ll go with her too.”

Finding how pious I suddenly was made you so delighted that you didn’t object at all. You knew that if I stayed back in Calcutta at this time, I’d get involved with Bindu’s mess again. You had a lot of anxieties about me.

We were about to set out on Wednesday; all the arrangements had been done on Sunday. I called Sarat and said, “By any means, you must bring Bindu over on Wednesday and put her on my train.”

Sarat’s face brightened up. He said, “Never worry, Sis. I’ll put her on the train and ride along with you all the way; it’ll be a free ticket for me too to see the Jagannath temple[11].”

Sarat came back the same evening. My heart sank just to see him back. I asked, “What happened, Sarat? Couldn’t get to do it?”

He said, “No.”

I said, “So, you couldn’t get her to come?”

He said, “There’s no need for it. Last night, she put fire on her clothes and committed suicide. There was a boy in their house whom I made friends with; he said she’d left a last note for you, but they destroyed it.”

All right, so there was peace now after all.

The whole community got fired up at the news. They said, “It’s now become like a fashion to put fire on yourself.”

You said, “It was too much of a drama.” It might have been. Yet, one must also find out why the fun part of the drama always went over the saris of Bengali women and not dhotis[12] of fearless Bengali men.

Bindi was truly luckless. When she lived, she got no fame for her beauty or other virtues; when she died, she did it in such an outdated way that nobody found it to be unique and worthy of compliments. Even at death, she made people angry.

Sister-in-law hid in her room and wept. But there was an element of consolation in her weep. After all, Bindi was indeed saved by the death. It could’ve been much worse if she had lived.

I came to the pilgrimage. Bindu didn’t need to come anymore, but I did.

I never really had anything in your family that one could call unhappiness. I never had any lack of food or clothes there; and whatever your brother’s character was, I couldn’t call you a person of low morale. Even if you had problems with your character, I could’ve survived more or less okay, blaming the universal god instead of the husband god, following the footsteps of my faithful sister-in-law. I would not want to bring complaints against you – that’s not the reason I wrote you this letter.

But I’m never going to return to your home at twenty-seven Makhan Boral Lane. I’ve seen Bindu. I now understand what exactly the status of a woman is in this world. I don’t want to be any part of it.

I’ve also discovered that even though she is a woman, God has not given up on her. However much power you’ve possessed on her, it all has had its limits. She is way over beyond her mortal life. Your feet are never so long that you could trample her for eternity. Death is mightier than you. She is noble in death – there she’s not just a Bengali household bride, not just a sister of a couple of cousins, and not just a deprived wife of an insane husband. She’s infinite there.

The music of death touched me deeply, and hurt me intensely through her. I asked my God: why was the most trivial thing in the world the most difficult? Why was this insignificant bubble within the walls of this alley so much of an obstacle? Why couldn’t I overcome the barrier of this door even when your universe with its six seasons invited me so cordially? Why’d I have to perish in this darkness bit by bit when I had such a life and a world you’d offered me? Would it be possible that this mundane triviality of everyday life with its obstacles, taboos and clichés would win and your universe of freedom and bliss lose out?

The music of death went on playing however; where was the wall built by the mason, where was the fence you built with all your restrictions of earthly laws – how could they confine people eternally and humiliate them? There flies high the victory flag in the hand of death! Oh Dear Middle Bride, never fear! It would be just a matter of moments before you could molt your Middle Bride-ship.

I no longer fear your alleys. I have the blue ocean in front of me, and I have the monsoon clouds over my head.

You’d covered me up under the darkness of your habits. Bindu came briefly and looked at the real me through the small openings on that cover. That girl totally tore up the rag using her own death. I came out and saw in amazement that I was full of dignity and glory. He who appreciated my unappreciated beauty now kept looking at me with the whole sky. The Middle Bride now died.

Don’t you think I’m actually going to die. Never worry: I’m not going to play that cheap-old trick on you. Mirabai[13] was a woman like me, and her shackles were no less heavy, yet she didn’t have to die in order to live. Mirabai said in her song, “Let my father rid of me, let my mother give me up, and let all the others do it too, but Mira keeps hanging on. Oh Lord, let anything happen to her, but she won’t give up on you.” That hanging-on itself is the true way to life.

I shall live too. I have lived.

Shelter-Severed Yours,

Mrinal

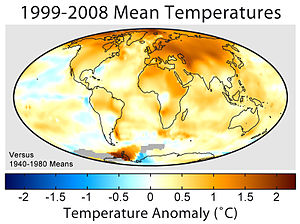

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia(Via Partha Banerjee)